Pat

Ciricillo's Piano:

Bix Beiderbecke's

Flashes and In the Dark

Introduction.

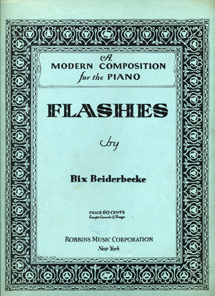

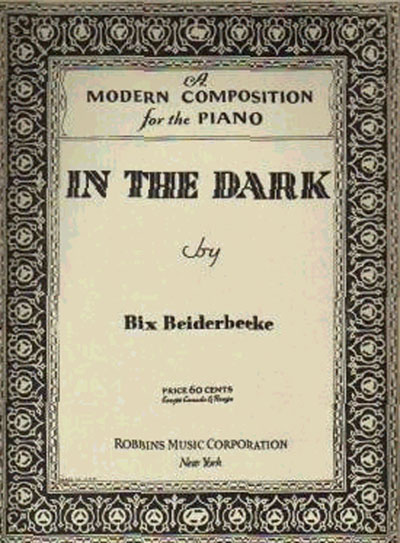

The

Robbins Music Corporation copyrighted Bix Beiderbecke's compositions Flashes

(E22489) and In

the Dark (E22490) on April 18, 1931. [1]

Bix composed these impressionistic pieces

in the

winter and spring of 1931 on a Wurlitzer piano that belonged to

Pasquale

"Pat" Ciricillo.

After blacking out in the middle of a solo during the October 8, 1930

Camel

Pleasure Hour broadcast, Bix Beiderbecke went home for rest and recuperation.

Bix

spent

the rest of the fall and the first two monts

of the

winter of 1930-1931 in his parents' home in

Pat

Ciricillo's Piano in the 44th Street Hotel

and Bix, 1930-1931.

Bix's next door neighbor in the

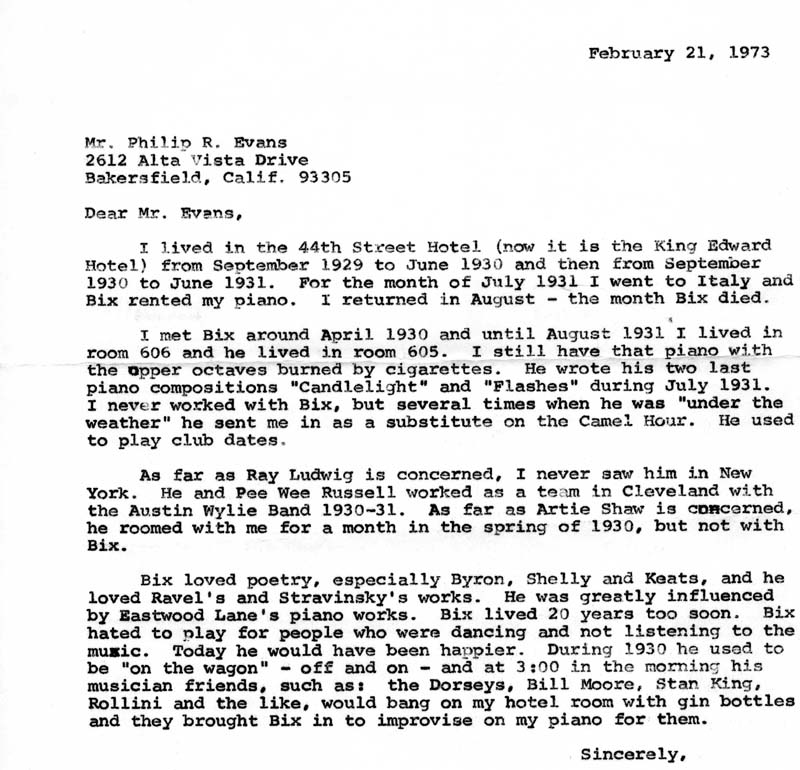

Pat wrote to Philip Evans, the Bix biographer, on February 21, 1973, [1]

"I met Bix around April 1930 when I lived

in the

For the month of July [1931] I was in

Pat's

piano is currently in the Museum in

The information on the card next to the piano reads as follows.

"Piano Played by Bix Beiderbecke.

Wurtlitzer Console. 1920's

This piano was owned by Pat Ciricillo

when he lived in room 606 at the

Bix joined in jam sessions Tommy and Jimmy

Dorsey,

Red Nichols, Adrian Rollini, Bud Freeman,

Mildred

Bailey, Eddie Condon, Hoagy Carmichael,

Pee Wee

Russell and others, often as late as 3 a.m. They stuffed paper around

the

hammers to keep the noise down.

Bix died on August 6, 1931.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank V. Smith"

From

my conversations with Joe Giordano and his interview of Pat Ciricillo,

[3] I pasted together the following information about the piano.

At the end of April 1930, Bix took

residence in room

605 of the

Pat secured a job in a summer resort for three months, beginning in

June 1930

and allowed Bix to use the piano for that

period. [2] Pat

returned to

Early in the 1970's Pat Ciricillo offered

to sell his

piano to record collector and Bixophile Joe Giordano for $50. Joe was

interested, but had no room for

the

piano in his apartment in

In

the Dark

and Flashes, Winter

and Spring 1931.

Pat Ciricillo reported that Bix

was composing "In the Dark" in the winter of 1931, using

Pat Ciricillo's piano. Jack Teagarden, who

had joined

Red Nichols at the Hotel New Yorker on February 8, 1931, roomed with Bix during the February 14-15, 1931 weekend.

Teagarden

confirmed Pat Ciricillo’s account. In a

telephone interview with Philip Evans [1] on February 18, 1960,

Teagarden

reported "I spent the weekend with Bix in

his

apartment. He was working on In the Dark and had only a

beginning and an

ending, being unable to connect the two. I whistled a bridge that I

felt would

fit. Bix was delighted and kept it in the

composition

that Challis scored."

Bill Challis, arranger with the Jean Goldkette

and

Paul Whiteman orchestras, transcribed all four if Bix 's piano

compositions, In

A Mist, Candlelight, Flashes and In the Dark, as well as Bix's sole orchestral composition, Davenport

Blues.

In a June 6, 1979 letter to Norman Gentieu,

Challis

commented on Flashes and In the Dark

as follows. [1]

"In the Dark had the same formula, main part rhythmic with a

melodic middle.

Flashes, Bix did in a hurry. he

wasn't working and he did the composition because he needed the money.

Jack

Robbins was willing to accept almost anything. Bix

would say, "I have another one." It was the only income he had going.

Flashes was done in the same format

as the

others, but required too much musical knowledge, too much musicianship

to

understand it.

If Bix had lived, he would have changed

the formula.

He'd have given it more thought and come

up

with

something different."

Pat

Ciricillo About

Bix.

As Bix's next door neighbor for over

a year,

and being a musician (trumpet player), Pat Ciricillo

got to know Bix reasonably well, and had

several

comments to make about Bix in letters to

Phil Evans

and in his interview with Joe Giordano.

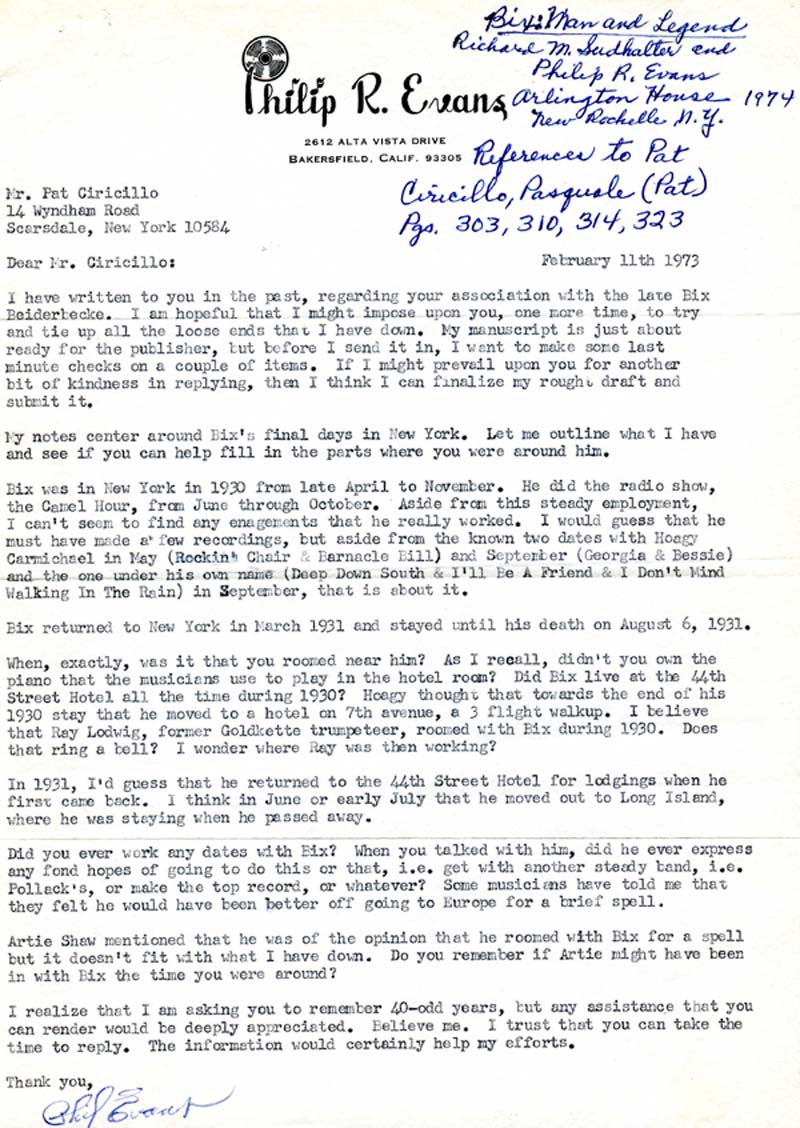

In response to Phil Evans letter of

February 11, 1973, (Courtesy of Robert Ciricillo)

Pat Ciricillo responded on February 21,

1973,

(Courtesy of Robert Ciricillo)

Interview

by

Joe Giordano, 1970s.

[3]

"Now

let me see what I can recall about Bix,

my old neighbor. The thing that I got about him is that he was a very

sensitive

person inside. People don't realize that he was a poetry reader; his

favorites

were Byron, Keats, and Shelley, since he kept their books on his desk.

And the

composer that influenced him the most in his piano compositions was

"The first notes I played in

"The first time I met Bix was in 1930,

although

I had seen him on stage in

"One of the things I remember is that when he was on the wagon, he

would

be in a sort of stupor. If you ever look at any of his pictures, he had

a stare

about him with the eyes that was penetrating. Then his friends would

come

around and bother him and he'd go back drinking. Gin mostly, or

straight

alcohol with a few drops of lemon juice."

In response to the question if he subbed for Bix

in

the Camel Pleasure Hour, Pat responded, "He used to send me in

occasionally when he wasn't up to it and, hell, I didn't mind; never

even took

his pay. Charlie Previn was the director

and I

believe it was in the Fall of 1930." [Bix played in the Camel Pleasure Hour from June

4, 1930 to

October 8, 1930.]

"Red and Bix were not really the same kind

of

players. Red was a very clever cornet player and he used a lot of Bix's ideas. He came from

When asked what was his biggest impression about Bix, Pat Ciricillo

responded, "Mainly that he was born too soon, and that he was

frustrated.

What he wanted most was for people to listen to those nice notes that

he used

to put in; there was a certin subtlety to

his style.

But the people wouldn't listen! They just wanted to dance to the music.

Later on,

however, they became more aware in the listening department. Actually, Bix was an odd figure in this country's musical

history. He

was probably the first white to be appreciated by black musicians. Let

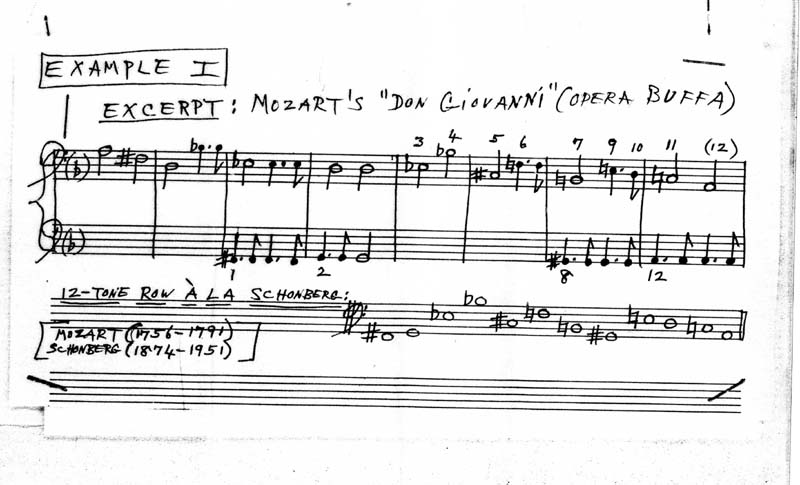

me show

you something as an example. Mozart, in his Don Giovanni opera buffa, gives us a foresight into the 12-tone

scale of

Arnold Schonberg. Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, etc. occasionally gave us an

inkling

of what was to come years later.

So

does Bix!

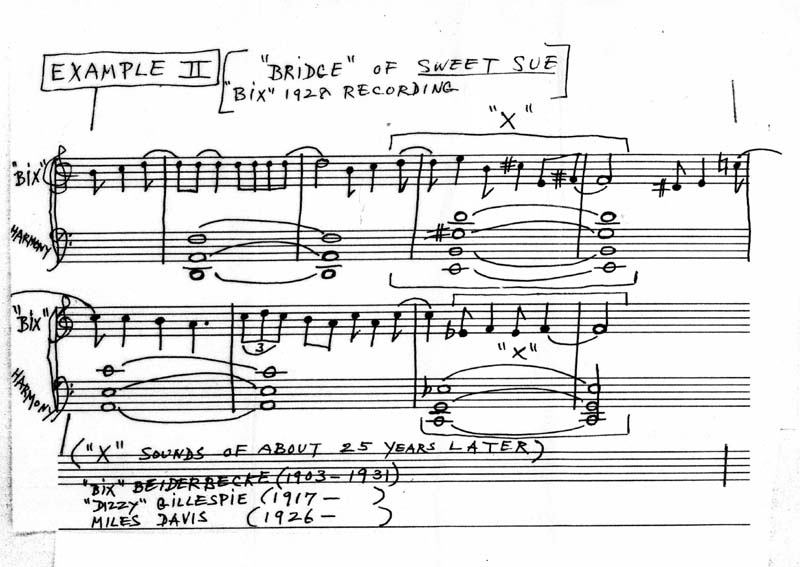

In the bridge of the Whiteman recording of Sweet Sue, Bix gives us a hint of Dizzy Gillespie's style

of a quarter

century later.”

A

Brief Biographical Sketch of Pasquale "Pat" Ciricillo.

Acknowledgements. I am grateful to Joe Giordano and Robiert Ciricillo for helpful discussions and their generous gifts of documents used in this article.

[1] Philip R. and Linda K. Evans, "Bix, The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story," Prelike Press, Bakersfield, CA, 1998.

[2] It is possible that Bix refined his composition Candeligths (copyrighted on Aug 29, 1930) in May- Aug 1930 using Pat Ciricillo's piano. However, most of the work on this composition was done in Davenport in the first few months of 1930. According to a Sep 24, 1973 letter from Bill Challis to Phil Evans, "When Bix returned to New York (end of April 1930) from his home in Davenport and declared himself ready with another composition, he had already titled it Candlelights. I had much less difficulty with the notation since it was practically set in his mind and thus it was just a matter of getting together and getting the work done."

[3] Joe Giordanos' original notes of the interview were kindly provided by Robert Ciricillo, Pat's son.