<>

| The

First Bix Lives Award |

Bix

Exhibit Hall |

Beiderbecke Memorial Garden |

Our

Room in the Beiderbecke Inn |

| Dr.

William Roba's Lecture |

Photos In The Musician's Union Building in

Davenport |

||

On Saturday, July 28, 2007, Rich Johnson was honored by the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society for his great contributions to Bixology. Rich is the first recipient of the "Bix Lives" award. I cannot think of anyone more deserving. For years, Rich has devoted all of his time, selflessly, in pursuit of his passion for all things related to Bix. Rich knows everything there is to know about Bix in Davenport and about Bix's family. For years, Rich generoulsy acted as Davenport's host for all visitors who came to pay tribute to Bix. Congratulations, Rich!

From the Quad City Times

Honor for a man who keeps Bix's spirit alive

By Bill Wundram | Saturday, July 28, 2007

Somewhere between Josh Duffee’s high society orchestra sweetly playing “I’ll Be A Friend Forever” and the brassy New Orleans All Stars blasting like dynamite — the first-ever “Bix Lives” award was put in the surprised hands of Rich Johnson on Saturday night.

It was a memorable moment at Davenport’s Clarion Hotel, of cheers and a standing ovation for this grand guy of jazz who knows so much about Bix that some think he is a member of the family.

The award was a commissioned 14-inch bronze of Bix, a good likeness of our golden boy, standing with legs crossed, bow-tied and a stubby cornet in hand.

“Already, we’re calling the statue ‘Oscar’ because we’ll be presenting one each year in the future,” says Ray Voss, Bettendorf, who holds the thankless job of being president of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society.

Rich, of Moline, was surprised, to say the least. A modest man, he smiled and muttered quiet words of thanks. Rich is not well; he has been in a long struggle with lung cancer but was determined to be at this year’s 36th Bix Bash. “I think this may be my last one,” he told me a few weeks ago. Still, he is surprisingly hardy and plays occasional Sunday morning brunch gigs on guitar at the Radisson Quad-City Plaza.

A tribute to Rich was written by Jim Arpy and read Saturday night by Jim Petersen, a Bix relative. Arpy called Rich “Our roving ambassador, our ‘Doctor Jazz’ … To all who have given their time and talents to making the Bix Festival grow bigger over the years, Rich Johnson is a treasured icon, always on the trail of undiscovered chapters in the life of Bix, his musical idol.”

Members of Rich’s family were at the presentation. They were aware of the award but kept it a guarded hush-hush. Only a few outsiders knew.

“It was one of the town’s best kept secrets,” says Josh, with his typical slick-back ’20s hair. “We played ‘I’ll Be A Friend Forever’ because it was one of Rich’s favorite Bix recordings.”

The idea for a statue and award was fostered by Al VanTieghem, a benevolent part-time resident of the Quad-Cities who sponsored Randy Sandke’s band at the Bix. There has been talk of some annual “Oscar” honoring the mission of Bix Beiderbecke and jazz bash, and Al told Ray Voss, “This is something the Bix Society should be doing.” He brought the idea to his family, and the Ruth and Albert VanTieghem Family Fund agreed to pay $3,300 for the bronze and its mounting.

Three months ago, sculptor Ted McElhiney began work on it, using paintings by Quad-City artist Ward Olson as models. Now that there is a mold, future annual Bix Lives awards will cost about $600.

All along, the bronze was meant to be of a casual, carefree Bix, smiling and with big ears. It’s said that his big ears made it possible for him to hear notes that no one else could hear.

The Official Certificate (click on link)

A Photo of Rich Johnson with his wife and son just after he received the award. Man standing behind is Bill Wundram.

Jim Petersen reading the Bix Lives Award to Rich Johnson.

Archival Center

Plans for the construction of a Bix Exhibit Hall and Archival Center in the Putnam Museum in Davenport, Iowa are progressing rapidly. The Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society and the Putnam Museum have reached an agreement for the construction of the Hall in the lobby of the Museum. The announcement was made in the Putnam Museum on Thursday, July 26, 2007 at a Press Conference according to the following schedule.

10:00 a.m. Welcome and announcement by Putnam Board Chair Dana Waterman

10:05 a.m. Dana Waterman introduces Ray Voss

10:05 a.m. Ray Voss, president of Bix Memorial Jazz Society, remarks

10:10 a.m. Randy Sandke, chair of Bix Hall Committee, remarks

10:15 a.m. Howard Braren, fundraiser of Bix Hall Committee, remarks

Check presentation by Statesmen of Jazz

10:20 a.m. Dana Waterman, closing remarks

10:25 a.m. Randy Sandke plays Bix's cornet

10:30 a.m. Conclusion of News Conference

Coverage of the press conference by the Quad City Times.

Bix hall to be built at Putnam Museum

By Alma Gaul | Thursday, July 26, 2007The complete story of jazz great Bix Beiderbecke — the Davenport native being celebrated this weekend — will be told in a new museum hall expected to open during July 2009 in the existing Grand Lobby of the Putnam Museum/IMAX Theatre.

Representatives of the Putnam and the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Society made an announcement of the collaborative venture Thursday while standing in a roped-off area of the lobby, showing the 1,300-square-foot footprint of the proposed hall. It will be located along the lobby’s east wall between the IMAX ticket area and the theater.The $1.382 million hall will be built by the jazz society, which will begin fundraising in January, with a hoped-for construction start in January 2009. The society will pay about $800 per month in rent to the Davenport museum, charge its own nominal admission fees and staff the hall with its own docents, said Howard Braren, who will head the fundraising efforts.

The hall will chronicle Beiderbecke’s life and accomplishments with separate stations for his high school days, the time he spent playing music on riverboats and in Chicago, his unique method of playing the cornet and his association with other great musicians of his era, including Louis Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, the Wolverines, Bing Crosby and Paul Whiteman.

The timeline will conclude with Beiderbecke’s last days in New York City, the train ride back home for burial and a replica of his tombstone in Davenport’s Oakdale Memorial Park. Multimedia exhibits will allow museum-goers to listen to his music.

Artifacts will include Beiderbecke’s cornet (a Vincent Bach Stradivarius model B-flat) and the family piano, both already in the Putnam, as well as new materials the society hopes to collect.

Those include all of the original record “pressings” of Bix playing — some 257 sides — that are owned by Joe Giordano of Freehold, N.J., said Ray Voss, president of the jazz society.

The society also hopes to acquire the actual stage Beiderbecke played on in Hudson Lake, Ind., Voss said. Beiderbecke performed at the Blue Lantern ballroom in the summer of 1926, a time that has been described as a turning point in his life. After standing vacant for many years, the building has been refurbished as a place used for wedding receptions and the like, but the present owners are willing to part with the stage, Voss said.

The Bix Beiderbecke Hall will have a roof and an accordion-style wall covered with Bix graphics.

Braren stressed that “there is enormous interest in Bix music worldwide,” and “we have jazz societies itching to come to Davenport to experience where Bix lived and played.”

Last year’s annual jazz festival attracted people from 23 foreign countries, he added.

The society has raised $35,000 toward the construction so far, including $10,000 each from the Riverboat Development Authority and from Vicki Palmer/Don Priter, as well as $5,000 each from the Ruth and Albert Van Tieghem Family Fund, the Howard and Ruth Braren Fund and the Statesmen of Jazz.

Alma Gaul can be contacted at (563) 383-2324 or agaul@qctimes.com.

JUST WHO WAS BIX?

BORN: Leon Bix Beiderbecke was born in Davenport during 1903 to upper-middle-class German parents.

CAREER: Beiderbecke began playing the piano when he was 5 years old. He bought a cornet when he was 16 and taught himself to play it with an unconventional fingering that was to characterize his playing. He played with the Wolverine Orchestra and Paul Whiteman, known as the “King of Jazz.” With Whiteman he performed his own piano composition, “In A Mist,” during a concert at Carnegie Hall in New York City. He died in a New York City hotel room at the age of 28.

LEGACY: True fans began the annual Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival in 1972 to celebrate his spirit.

SITES ASSOCIATED WITH BIX:

-- His boyhood home at 1934 Grand Ave.

--His grave at Oakdale Memorial Park

-- First Presbyterian Church, where his family worshiped

-- His grandparents’ home at 532 W. 7th St., which is now a bed-and-breakfast inn

--Central High School

-- Places where he played, including the Blackhawk Hotel, the Col Ballroom and Danceland.

-- A bust in LeClaire Park that includes this famous summation from musical great Louis Armstrong: “Ain’t one of them play like him yet.”

—Quad-City Times

Press Release and Photos of Plans. (click on link)

Oakdale Cemetery

Davenport, Iowa

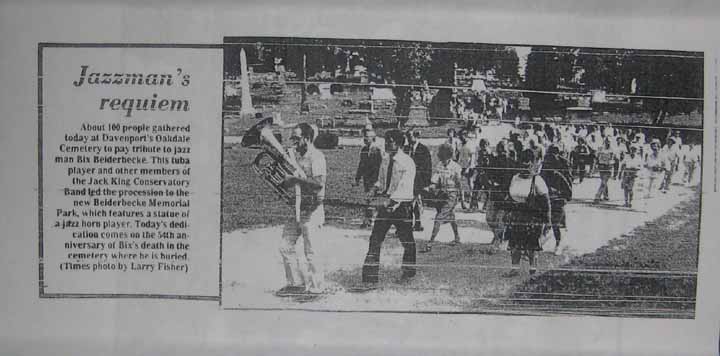

According to the Quad City Times, a statue of Bix Beiderbecke was dedicated in Oakdale Cemeteray on August 6, 1985, exactly 54 years after the death of Bix Beiderbecke in Sunnyside, Queens, New York The following article was published in the August 7, 1985 issue.

The Saints Came Marching In

It was a jovial morn yesterday, with Tom Tallman's Dixieland band marching to "The Saints." Tom Priester, the prexy of Oakdale Cemetery's board of trustees, was dedicating the new jazz statue to Bix, and commenting: "Bix and I had something in common. We both attended the same prep school (Lake Forest). Both of us got kicked out. Bix's departure had something to do with playing too much jazz in Chicago. Mine had something to do with Beer."

When it was over, a happy Priester said, "It's a beautiful day. Make yourself at home looking around the cemetery."

However it is you make yourself at home around a cemeery," mused Moline's Frank Mahar.

The statue is no longer in the cemetery. According to Gerri Bower and Jim Petersen, the statue was stolen at some time. It was replaced by a plaque that reads

Dedicated Aug 6, 1985

Addendum, Aug 14, 2007

From the QCTimes, Aug 6, 1985.

I am grateful to Gerri Bowers for sending me a copy of the article.

Beiderbecke Inn

Surrounded by Bix

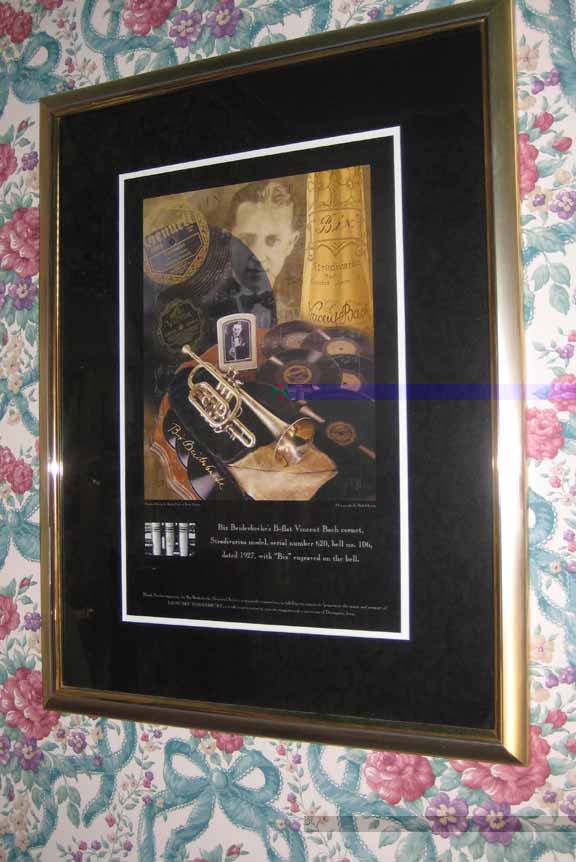

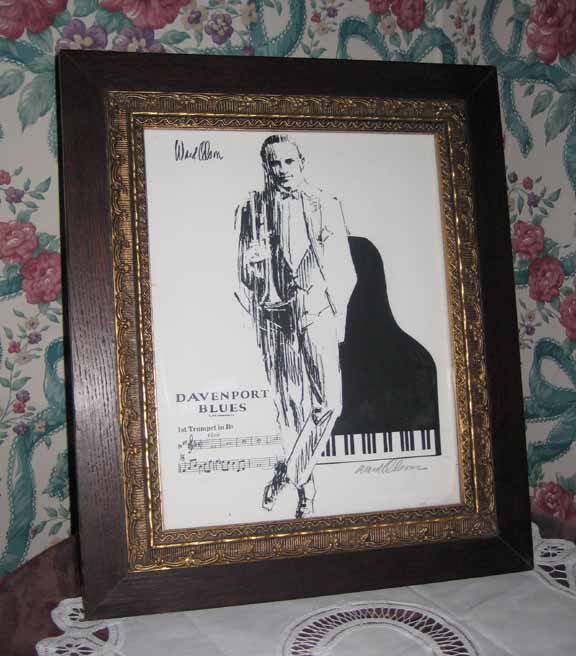

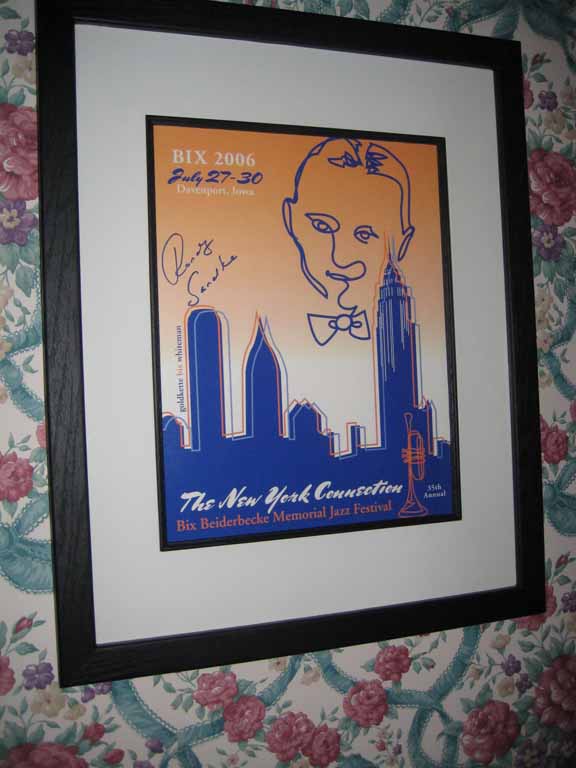

There are four rooms in the Inn: the Victorian Room, the Bix Room, the Tower Room and the Mississippi Rose Room. Of course, we stayed in the Bix room.

There are Bix paintings and posters on the walls of the bedroom as well as the bathroom.

Bob Christansen's Montage

There are five paintings by Ward Olsen.

There are three posters from past Bix Festivals.

The Beiderbecke Inn is a delightful place. Not only because one gets the magical feeling of Bix having been there frequently, but also because of the warm hospitality of the owners, Pam and Dennis Laroque.

Uploaded Aug 13, 2007

"German-American Influences On Bix."

One of the lectures at the festival was by Dr. Bill Roba, a history instructor at Scott Community College. The title of his lecture was “German-American Influences On Bix.” The Quad City Times of July 28, 2007 provided a summary of Dr. Roba’s remarks. The complete article by Mary Louise Speer follows.

*********************************************************************************

German heritage influenced Bix's music

By Mary Louise Speer | Saturday, July 28, 2007

So much is known about Bix Beiderbecke, the talented young cornet and piano player who wowed audiences during the Jazz Age of the 1920s.

Bill Roba, a history instructor at Scott Community College, highlighted lesser known facts of the German-American influences on Bix during an afternoon of seminars Friday given by jazz experts at the Clarion Hotel, Davenport.

The topics ranged from “Copying Bix” by Albert Haim to “Bix and New Orleans” by Bruce Boyd Raeburn as well as free range discussions with Phil Schaap and Randy Sandke.

The series was offered by the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society as part of the 2007 Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival.

“I don’t think this is an aspect of Bix we give much thought to, but he had a German heritage,” said seminar emcee Steve Trainor.

Certainly the world Bix lived in, and his family and education, influenced his outlook on life and music. In the early 1920s radio played an increasingly important role in helping people get acquainted with musical styles they might not have been exposed to elsewhere.

“Of the 8 million Germans who came to America, 40 percent of them came to the Midwest and this would have an influence on Bix’ music,” Roba said.

Possibly the most important person and influence on Bix was his grandmother Louise Beiderbecke.

Bix’ grandparents, Louise and Charles Beiderbecke, were very much a part of the German society in west Davenport. They lived in a mansion in that end of town with access to German-flavored attractions such as Schuetzen Park with its popular music offerings and the Turner Hall.

Bix’ first music lessons even came from German-American teachers.

His mother Agatha Beiderbecke, on the other hand, was very much an American mom and their family lived in the “more American east side of Davenport,” Roba said.

Agatha played the organ at the family’s church, First Presbyterian Church of Davenport.

The Beiderbecke family was well thought of in Davenport and, Roba said, World War I (1914-18) must have caused some moments of private agony.

During Bix’ time at Davenport (now Central) High School, the anti-German sentiment spilled over into a textbook burning that was evidently countenanced by faculty.

“We need to use some educated guesses that this must have had some effect on Bix since he was just starting high school,” Roba said.

The high point of high school for Bix was performing with his quartet and taking time to savor music events happening in the world around him. He liked keeping up with the latest musical trends, Roba said.

Eventually his love for the emerging musical form of jazz would propel him into the greater world with influences on his music from New Orleans jazz players and especially jazz saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer.

*********************************************************************************

In the last 15 minutes of his lecture, Dr. Roba went on at length about Bix’s arrest of April 22, 1921. He provided some new pieces of information. Preston Ivens, the father of Sarah, the girl allegedly involved in the incident, had a brother killed in World War I. Furthermore, Dr. Roba informed the audience that Preston Ivens was a strong advocate of the “100 percent American” movement prevalent as the US entered World War I.

Dr. Roba suggested that the reason for Bix being enrolled in Lake Forest Academy in the Fall of 1921 was the alleged incident of April 21, 1921. Available documentation on the arrest is provided in

http://www.network54.com/Forum/27140/message/978897881/The+Available+Documentation

There are other plausible explanations: Bix's academic work was very poor in high school - he

had failing grades in 9 of the 23 courses he took in 1918-1921: a failing rate of 39 %; Bix did

not graduate from high school at the same time as his classmates; Bix was frequently absent

from school in 1918-1921: 154 days in the academic years 1918-1919, 1919-1920, and

1920-1921. I will admit that the alleged incident with Sarah Ivens could have been a contributory

factor for the decision to enroll Bix in Lake Forest Academy. However, there is no evidence that

it was the major reason, and in fact that it was a factor at all. As a matter of record, the relations

of Bix with his family were quite close in the summer of 1921.

Towards he end of his lecture, Dr. Roba asked what had happened to all the money that Bix earned as a professional musician. Dr. Roba suggested that Bix was paying back the money that his father had paid Preston Ivens to drop the charges against Bix. This is sheer fabrication, and there is not a single shred of evidence for this outrageous supposition. It is well known that Bix was rather careless with money (once Jimmy McPartland asked him for a $10 loan, and Bix gave him $100) and that he lost quite a bit of money in the market crash (investments made for him by his sister; see liners by George Avakian in “The Bix Beiderbecke Story,” set of three Columbia LPs).

I searched for Preston Ivens in ancestry.com. Preston R. Ivens married young. The 1910 US Census finds him at age 18, occupation dealer for real estate business, living in Chestertown, Maryland with his wife Mary, age 18, and son Preston R., age 1. In 1917, Preston Ivens registered for the draft. He lived in Philadelphia with his wife and three children. He described himself as of medium height, stout, brown eyes, brown hair and bold. In 1920, Preston, age 28, occupation merchant in grocery store, resided in Philadelphia, PA, lived with his wife Mary, age 28, son Preston R., age 10, son William H., age 9, and daughter Sarah A., age 4. Preston Ivens and family moved to Davenport in 1921, where Mr. Ivens enrolled at the Palmer School of Chiropractic. From the SSDI, I learned that Preston Ivens was born on Jul 15, 1891 and died in Houston, Texas, in June 1969. His son, also named Preston, was born on Sep 7, 1909 and died in July 1969.

In searching information about Preston Ivens, I discovered that his grandson, Preston Ivens, III

lives in Sweet Water, Texas. I asked Gerri Bowers to call him and find out what he knew about

Davenport and Bix. It turns out that he did not recognize the name Bix Beiderbecke and had,

at best, a vague recollection that his grandfather had lived in Davenport. Gerri asked him if

Sarah's daughter, who also lives in Texas, might have some information. Preston responded

that he was in close contact with his cousin and that she would not be of much help either."

Dr. Roba's lecture on German-American influences on Bix prompted me to read about he status

of Germans in the US during and after World War I. Moreover, this point may have some

connection with Preston Ivens accusations of alleged acts by Bix. First I note that, according to

Dr. Roba, Ivens had lost a brother in World War I and was an advocate of the “100 % American”

movement. Second, I note that Ivens was living in Philadelphia when the US entered World War I.

I further note that Philadelphia was one of the centers for the movement that promulgated

“100 percent American” philosophy.

The following information and quotes are from “Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity” by Russell A. Kazal, Princeton University Press, 2004. First, some general comments about the disappearance of German influences in the US. “The eclipse of German-American identity today is all the more startling, given its condition at the beginning of the twentieth century. Then, German Americans were perhaps the best-organized, most visible, and most respected group of newcomers in the United States. Germans, whose migration to America peaked in the 1880s, made up the largest single nationality among the foreign-born during the 1910s, greater in number than the Poles, Italians, and other southern and eastern Europeans of the ‘new immigration.’ The National German-American Alliance, a federation of ethnic associations, laid claim by 1914 to more than two million members. Before the First World War, the Germans were widely esteemed as ‘one of the most assimilable and reputable of immigrant groups’; a group of professional people surveyed in 1908 ranked German immigrants ahead of English ones and, in some respects, above native-born whites.” Part of the explanation for the decline in German influence lies in the entry of the US in World War I. “The most obvious relates to the contingencies of twentieth-century history. That century saw the United States fight two world wars against Germany and witnessed the genocide perpetrated by the Third Reich; it therefore left Americans with few incentives to identify with a German ancestry. Even before those events, institutional German America--which encompassed everything from secular gymnastic and singing societies to German Lutheran congregations and German Catholic national parishes--was unraveling. Historians such as John Hawgood once pointed to the intense nativist backlash that accompanied American intervention in World War I as the key to the destruction of this ethnic world.” The author then explains the essence of his book. “I address the issues of assimilation, pluralism, nationalism, and race that the German-American paradox raises by reconstructing the fate of that group in one such place: Philadelphia from the turn of the twentieth century to the 1930s.” and one of the reasons why he chose Philadelphia, “The National German-American Alliance, which rallied German associations across the country to resist assimilation, was founded in the city in 1901 under the leadership of a coterie of local middle-class activists. One of them, Charles J. Hexamer, served as the organization's president and guiding spirit until 1917.” He further writes in an explanation of the decline of German ethnic identity, “Today's marked submergence of German-American ethnicity owes a great deal to the anti-German backlash of the First World War, yet that was just one of several developments that came together during the 1910s and 1920s to reshape German Philadelphians' sense of self. Those developments also included the rise of a narrower, more conformist American nationalism that discredited older, pluralist views of the nation; a related tide of racialized nativism.” “The event that precipitated those developments was, rather, the First World War--the subject of part 3. Initially, the European war actually heightened the ethnic consciousness and unity of those Philadelphians of German background who remained within the Vereinswesen, as chapter 7 describes. Many middle-class activists, socialist workers, Catholics, and Lutherans rallied to Germany's defense between 1914 and 1916. Yet the neutrality period also saw a reaction among Anglo-Americans and other non-Germans against such ethnic activism, a backlash expressed in attacks on the national loyalty of ‘hyphenated Americans’ and, eventually, demands that they be ‘100 percent American.’ With America's entry into the war, this ‘antihyphen’ movement metamorphosed into an anti-German panic. What began as a suspicion of German Philadelphians as potential spies and saboteurs mushroomed into a general assault on German ethnic expression itself and on the very legitimacy of views of the nation--like the National Alliance's--that allowed for a degree of ethnic separatism and, hence, cultural pluralism. Fed in part by the federal government's effort to mobilize support for the war, the panic led to the destruction of the National Alliance, the ending of German instruction in the city's public schools, and the hounding of ordinary German Philadelphians, at times by mobs. As a result, the public expression of German ethnicity became virtually impossible during and immediately after the war and remained problematic thereafter.”

The environment for people of German descent in Davenport (Scott County) was not any better. According tohttp://www.qcmemory.org/Default.aspx?PageId=242&nt=207&nt2=239

“In the decade before the United States entered the War, [this World War I] Anti-German sentiment rose to an almost ridiculous level, even in Scott County, where a considerable percent of the population were of Germanic descent. Local ordinances were passed to prevent the German language from being spoken in public, pre-German books were removed from library shelves, and many citizens of German birth were rounded up and interrogated about their loyalty to the United States. Many German businesses changed their names in order to show patriotism and to stay in business.” According to http://www.qcmemory.org/Default.aspx?PageId=226&nt=207&nt2=222 “September 7, 1918—Der Demokrat, Davenport’s German language newspaper, publishes its last issue due to anti-German sentiment during the years of World War I.”

In view of all this information, it may be pertinent to ask, on the basis of Dr. Roba’s report that Mr. Preston R. Ivens had strong anti-German feelings in the years after World War I and espoused the “100 percent American” philosophy, is it possible that his accusations against Bix were somehow colored by his prejudices?

Uploaded Aug 17, 2007. I am grateful to

Gerri Bowers for calling Preston Ivens, III

Union Building In Davenport

I visited the Musician's Union Buidling in Davenport on Monday after the festival. Forumite Sue Fischer was there taking pictures and consulting the archives for her research.

Outside View of Building.

A Photograph of Paul Whiteman as a Roman Emperor.

A pictorial interpretation of Paul Whiteman, "Emperor of Jazz."

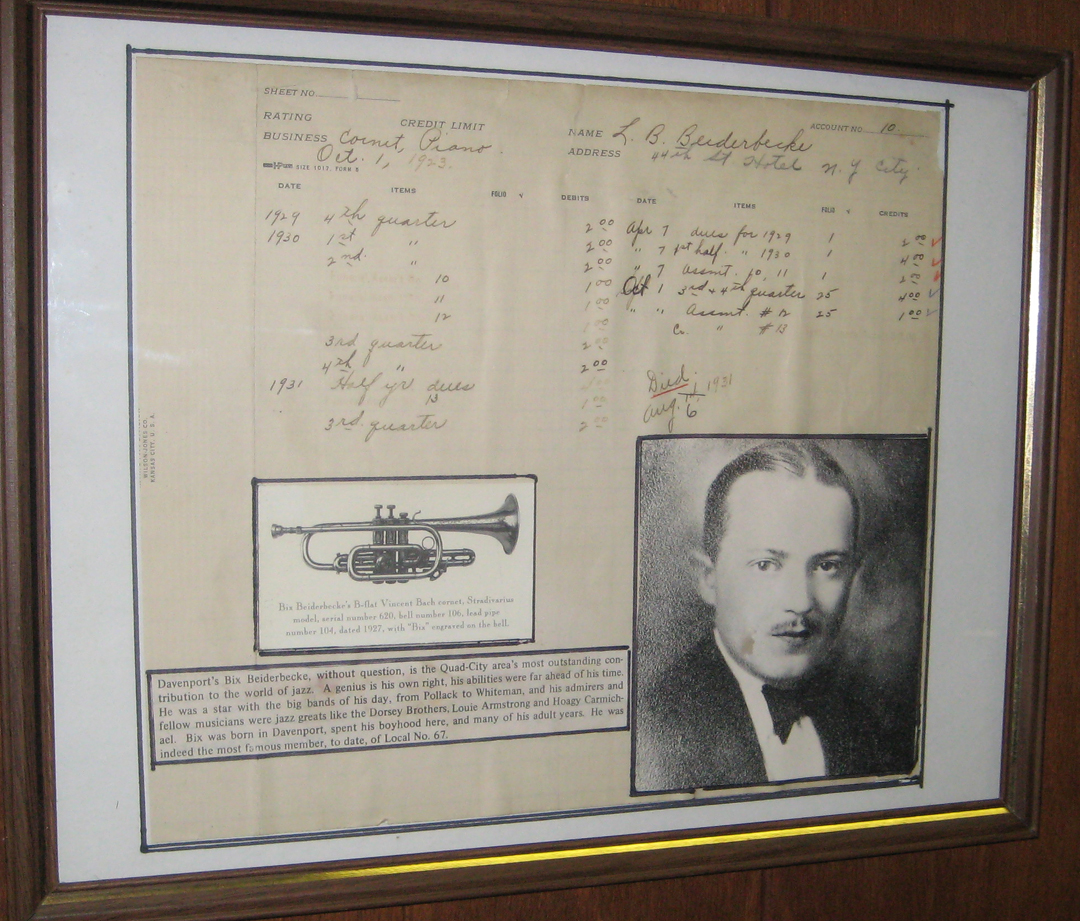

Bix Beiderbecke's Union Dues Document, Framed and With Images Added.

Note the error in the brief biographical sketch. Bix was never a member of the Pollack band. We see that Bix became an union member on October 1, 1923 and that he pai his dues through the end of 1930.

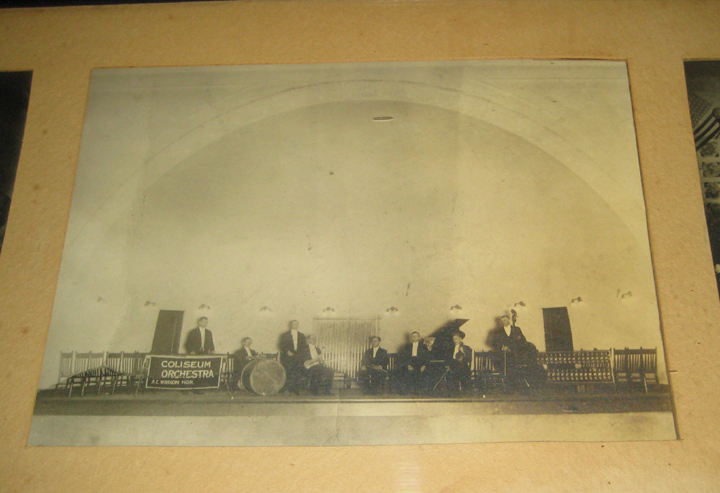

Doc Wrixon's Orchestra.

Bix played with "Doc" Wrixon's Orchestra aboard the S.S. Capitol from July 6 to July 15, 1921. Accoridng to Evans and Evans, "Bix did not have a union card and was forced by the musician's union to leave the Capitol band." The Wrixon band must have been a prettty prominent band in Davenport. They played in the Coliseum Ballroom and at the wedding of Mary Louise (Bix's sister) in the ballroom of the Davenport Outing Club.

Here are three photos of Coliseum "Doc" Wrixon's band.

Uploaded August

23, 2007.