"Finding Bix: The Life and Afterlife

of a Jazz Legend"

By Brendan Wolfe.

The University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, 2017.

A Review by Albert Haim

Stony Brook, June 2017.

Introduction.

“Finding Bix” by Brendan

Wolfe is a self-centered account of the

author’s efforts to “find Bix.” A more accurate title would be “Finding

Brendan

Wolfe and the Meaning of Calathumpic.” [Note 1]. When I read a book or

an

article, the first thing I look for is a statement of purpose, either

in the

introduction or early in the text. I could not find such a statement

under the

torrent of words in “Finding Bix” until page 64 “who was Bix

Beiderbecke and

what else didn’t I know about him?” and page 74: “this mission of

searching

Bix’s personality for clues to his music.” The latter is not what I

found in

“Finding Bix.” The music is presented as an after thought and treated

in a very

superficial manner. There is a general statement of purpose in the page

for

“Finding Bix” in the

- “Bugles for Beiderbecke,” by Charles Wareing and George Garlick,

London,

1958.

- "Bix Beiderbecke" by Burnett James.,

- "Bix: Man and Legend" by

Richard M. Sudhalter and Philip R. Evans with William Dean-Myatt,

NewYork,

1974.

- "La vita e la leggenda di Bix

Beiderbecke" by Aldo Lastella,

- "Bix Beiderbecke: Sein Leben, Seine Musik, Seine

Schallplatten" by

- "Bix Beiderbecke: Jazz Age Genius" by David R. Collins,

- "Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story"by Philip R. Evans and Linda

K. Evans,

- Countless chapters in jazz history books and articles in magazines.

- A set of set of 20 LP's, "Sincerely, Bix Beiderbecke," issued in

1988 and accompanied by a comprehensive booklet with detailed

information about

Bix’s life and music .

- A set of 12 CDs, “Bix restored” issued beginning in 1999.

- Innumerable LPS containing Bix’s

recordings and detailed information about Bix’s life and music. These

were

issued beginning in the 1950s, including the legendary set of George

Avakian’s

Columbia LPS where many current Bix admirers learned about Bix’s music.

“Finding Bix” corrects

the previous ignorance of the Bix Beiderbecke

literature, but, as explained below, some crucial pieces of information

are

still missing.

General Comments.

There is no new factual

information about Bix in

“Finding Bix.” The book consists of quotations from earlier books (both

fact

and fiction), articles, films (one a documentary, the others fiction),

postings

in social networks, private communications, many of them anonymous, and

the

author’s remarks. Bix did no leave diaries or gave interviews (except

one,

plagiarized, as detailed in “Finding Bix”). The only primary source

about Bix

consists of the letters he wrote to his family mostly in 1921-22 and a

few in

1931. There are several second-hand accounts from some of the people

who knew

Bix personally. The majority of these accounts –interviews via letters

and

telephone conversations a few decades after Bix died– come from Phil

Evans’s

50-year research about Bix. These second-hand accounts are necessarily

colored

by the passing of time and faulty recollections. Moreover, the comments

of

Bix’s fellow musicians are often anecdotes and chronological

information that

shed little light about the “essence” of Bix.

Thus, the effort

expended in “Finding Bix” (which I take it to mean to

find the real Bix) is necessarily a failure, as acknowledged by the

author

himself. The author reports what others have said about Bix in a

disorganized,

rambling, verbose, pretentious and repetitive style. But that is not

the most

serious problem with the book. To me, one of the major flaws is the

false

equivalence assigned by the author, in his efforts to “find Bix”, to

books and

articles by scholars and historians on one hand; and on the other hand,

inventions in works of fiction (books and films), casual comments from

contributors in social media/discussion groups, and private

communications,

often from unnamed individuals. The conflating of fact and fiction is a

very

serious fault that invalidates the few inferences the author draws.

I will provide a few

examples.

- In pages 142-143, the

author provides some information from the

detailed biography of Trumbauer by Evans and Kiner. Wolfe cites the

circumstances under which Goldkette hired Bix in 1926. In the second

half of

page 143, the author brings in an invented dialogue between Bix and

Tram from

the Avati’s film. If the goal is to “find Bix,” then it seems to me

that

bringing in fictional material and mixing it with fact is

counterproductive and

misleading.

- In page 154, Wolfe

cites Kraslow’s (the rental agent for Bix’s last

residence) account of Bix’s last days and then throws in a quotation

from

Turner’s fiction book “1929.” How does the quotation from a fiction

book help

“Finding Bix”?

- In page 90, Bix and

the fiction character Rick Martin in Dorothy

Baker’s novel “Young Man with a Horn” are both viewed as victims:

“Better make

Rick, like Bix, the perpetual victim.” In fact, according to Wolfe the

real

person and the fictional character are fused together as one: “Rick

will always

be Bix, and Bix will always be Rick.” It sounds good, but it is a

preposterous

proposition. If Wolfe is trying to “find Bix” he is not going to find

him in an

invented character of a novel, regardless of

how much Bix was an inspiration for Dorothy Baker to create Rick

Martin

in her novel “Young Man with a Horn.” See also page 3: “Someday when

I’m really

good, I’m gonna do things with this trumpet nobody’s ever thought of

doing,” a

wide-eyed Douglas (actor Kirk) tells Doris Day.” And later, “Poor Kirk.

I

always feel bad for him at this moment---stamps?!?--- even as I am left

wondering what part of all this is Bix and what part is legend.” Does

Wolfe

seriously expect to “find Bix’ in the words of an actor playing a

fictional

musician in a movie based on a novel?

More General Comments.

From the University of

Iowa Press webpage about

“Finding Bix”: “What follows, though, is anything but straightforward,

as Wolfe

discovers Bix Beiderbecke to be at the heart of furious and ever-timely

disputes over addiction, race and the origins of jazz, sex, and the

influence

of commerce on art. “

I will discuss each of

these topics now.

Race and the Origins of Jazz.

While Bix was alive, race in jazz was not an issue. Of course, there

was

segregation, but that was a part of life in

Sex.

Wolfe brings in two sex issues about Bix: 1. his arrest in April 1921

for

his interaction with 5-year old, visually impaired Sarah Ivens; and 2. his alleged homosexual encounter with

Ralph Berton’s older, gay brother. Bix’s arrest is first

mentioned/hinted

briefly in pages 31, 34, 62. As a matter of fact, the mention in page

34

consists of a four-line chapter!

I have the suspicion

that the brief, repetitive specification is done

for dramatic effect, with the idea of whetting the reader’s appetite. I

think

it is a cheap trick.

All details associated

with the arrest, including all extant documents

and extensive discussions have been covered ad nauseam in social

websites,

(Bixography Forum and Facebook), in Rich Johnson’s “The Davenport

Album” and in

Jean Pierre Lion’s “Bix: The Definitive Biography of a Jazz Legend.”

All Wolfe

does is rehash the available information and provide the opinions of

several

Bix scholars/aficionados, but not his own conclusions.

Just a few

clarifications. Wolfe quotes what Geoffrey Ward writes about

the arrest in his “Jazz: A History of America’s Music.” “a lewd and

lascivious

act with a child-apparently just a fellow teenager”

Evidently this is a false account. The child

was five-years old. It turns out that Ward obtained the information

about the

girl being a teenager from Phil Evans. On August 10, 2002, I reported

that

Evans had misled Ward. http://www.network54.com/Forum/27140/message/1029004042

Chapter 36, page 125

begins with an account of Bix’s arrest. But by

page 127, Ralph Berton’s alleged fling of Bix with Gene Berton is

brought in

and this is followed by a discussion of Sudhalter’s “Ominous Note.”

Then Wolfe

writes: “Sudhalter never explains how this context might shed light on

whether

Bix was gay, but it’s not difficult to connect the dots.” First, Bix’s

arrest

and Berton’s alleged fling with his gay brother Gene have nothing to do

with

each other. Wolfe acknowledges that “Whether Bix was gay, bi- or

anything else

should be irrelevant to the facts of April 22, 1921-and yet it never

has been.”

No documentation for the connection between the arrest and the fling is

presented – and I don’t know of any such connection in the Bix

literature- so

why bring the fling when discussing the arrest? Moreover, the

connection of

Sudhalter’s Ominous Endnote and an allegation of Bix being gay is

highly

misleading and perhaps dishonest: Wolfe knew the facts. He had asked

Sudhalter

in 2003 about the facts behind the “carefully husbanded documentation.”

Sudhalter’s answer was clear: he was referring to the arrest, not to

homosexuality on the part of Bix. Why the unjustified innuendo?

The last point. Wolfe

fails to report that the Ivens family returned to

Alleged Homosexual Encounter.

This comes exclusively from Ralph Berton’s “Remembering Bix.” There is

no other report. There are several mentions of the incident. First, in

another

very short chapter (chapter 21, 14 lines) which cites a “fling” and

ends with

the sentence: “Wait a minute,” he told his brother. “What do you mean

by a

fling?” Is again Wolfe presenting a bit of a preview for dramatic

effect,

without providing all of the information in one location? Another brief

mention

in page 128: “Ralph Berton’s bombshell claim that Bix had had a “fling”

with

Berton’s brother Gene.” And in page 129: “When Ralph Berton’s book was

published, the homosexual story was a big shock for Bix fans.” Finally,

in more

detail in pages 133-134, Wolfe again uses the misleading technique of

conflating reports in a pseudo-biographical account with lots of

fabrications,

Berton’s “Remembering Bix,” and a novel, Laura Mazzuca Toops “

The Influence of Commerce on Art (and

Authenticity).

This is a well

visited subject and includes the myth that Bix had “sold out” when he

accepted

Whiteman’s offer and, except for a few solos, was very unhappy because

he no

longer could play “authentic” jazz. Some of this has been debunked by

Sudhalter

and Evans in 1974 and by Evans and Kiner in 1997. Why bring it back in

2017?

Jazz snobs are always emphasizing the question of “authenticity.” What

is

unauthentic about a hot dance band recording by Jean Goldkette with

Bix? It may

not be “real jazz” according to jazz snobs, so what? We must realize

that Bix’s

career was mostly that of a dance band musician.

Bix’s Relations With His Parents.

Several Bix biographies discuss the

failure of Bix’s parents to support Bix’s decision to become a dance

band/jazz

musician. Wolfe echoes: “And his parents’ failure can be summed up

neatly in

this single anecdote (the story of the unopened records, which I cover

below).”

It is not unexpected that for Bix’s parents, an upper middle class

couple, born

and raised in the Victorian era, Bix’s chosen career as a dance

band/jazz

musician was regrettable. However, the Beiderbecke family was

close-knit and

Bix’s parents helped Bix whenever he was in need. The failure of Wolfe

to point

this out represents, in fact, a distortion. There is ample evidence of

a

genuine love in the family. Two examples will suffice.

- A letter of condolence on the occasion of the death of Bix's

grandmother. The

letter starts with "Dearest Dad" and later continues as follows

(verbatim, with errors uncorrected; underlined text is my own.) It was

written

from

- Bix spent Feb 1929 at home, recuperating from his breakdown in

"Bickie is still with us. We dread to think of his leaving because he

is

such a

peach to have around & heaven only knows when he will spend another

vacation with us.

With the exception of a slight cold he's feeling fine but believe me,

he needed

the rest he had here & I'm sure he is in the pink of condition now

to get

back into the harness.

Whiteman plays in

We dread to think of his leaving because he is such a peach to have

around & heaven only knows when he will spend another vacation with

us."

Of course, Bismark was concerned about Bix, but the above sentence is

very

revealing of the love Bismark felt for Bix. Bismark's own words about

his son

to his daughter mean a lot more than anything that anyone has ever

written

about the interaction of Bix with his parents.

Note: Whiteman played the Old Gold Hour on Apr 8 from KOL in

Why didn’t Wolfe include

these two letters in “Finding Bix.”? In my

opinion, they represent crucial documentation in any effort to “find

Bix.”

The Unopened Boxes of Records.

This has become one of the most widely

circulated stories about Bix. Wolfe appears to accept the accuracy of

the

unopened boxes of records story (pages 121-122). However, he also

reports Scott

Black’s account that the records were not Bix’s, but records by the New

Orleans

Rhythm Kings. Evans and Evans write: “Bix’s life has been filled with

many

rumors and colorful stories, none has been more damaging then the

“false” story

of his finding unopened boxes of records he had sent home over the

years.”

Moreover, considering that this story is included in most Bix

biographies and

biographical sketches, I am surprised that Wolfe does not provide more

information

and fails to analyze the story in detail in his quest to “find Bix.”

Here are

some of the missing data.

- A portion of a letter from Bruce Foxman to Phil Evans dated March 10,

11 1964

in which Bruce tells Evans the result of his interview of Esten

Spurrier. Here

are the exact words from Bruce's letter to Phil. The account is

slightly

different than what Spurrier told Sudhalter in

- There is a letter from

Bix’s brother to Evans. Charles B. Beiderbecke

(12/4/59) totally dismissed this story: "Bix never did send home any

test

pressings or recordings."

- There is another fact

to be taken into consideration. Bix’s brother,

beginning in 1925, was the manager of the Victrola division of the

Harned and

Von Maur Store in

It seems to me that

Wolfe, in his efforts to “find Bix,” should have

analyzed the whole question of the unplayed records and/or unopened

boxes of

records more thoroughly and provide any conclusions he might have

reached..

A Few Detailed Comments.

- Page 17. “Rich

Johnson, a tall and ornery Bixophile.” A gratuitous

and patently false comment about one of the nicest guys in the world of

Bix.

Rich got along very easily with everyone. In the world of Bixophiles,

where

personal enmities are common, Rich was a notable exception. He even got

along

with some of the nastiest Bixophiles.

- Page

166. "Chris Barry in

pursuit of the piano..." That is incorrect. Chris's discovery of the

true

identity of Alice Weiss O'Connell had nothing to do with the piano.

Chris wrote

in the Bixography Forum in April 2009: " it would seem that Bix

inadvertently had the name associations reversed. By that I mean Weiss

was

- Pages 32-33 and 78-81.

Wolfe often treats a subject in installments.

Here is another example. First cited and discussed briefly in pages

32-33 and

then in more detail in pages 78-81, readers will find what I can only

describe

as a pompous and overblown analysis of Gregory Elbaz’s graphic novel

“Bix.” I

wonder how a surreal graphic novel can help the author “find Bix.”

Wolfe

mentions me twice in the pages cited above. 1. “Perhaps flipping

through is all

Albert Haim did.” Perhaps, Wolfe has no idea of how I looked at the

book. 2.

"Albert Haim is bloody Saint Giles protecting his poor beast from the

slings and arrows of vulgar men." “Bloody Saint Giles”? Bix, my “poor

beast”? My understanding is that Saint Giles was the patron of beggars

and

cripples, certainly a totally inadequate description of Bix. Moreover,

I do not

consider myself a Bix protector, but a Bix researcher who tries to

dispel

incorrect information and to express his opinion of all things related

to Bix

in a direct manner.

- This is irrelevant to

the subject of Bix and is admittedly

nitpicking. But as a teacher for nearly 50 years and an admirer of

Jorge Luis

Borges, I find the following error offensive. In page 6, Wolfe writes

“If this

were Borges, there might be talk of el asombro or la sagrada horror.”

Horror in

Spanish is a masculine noun; the correct form is “el sagrado horror.”

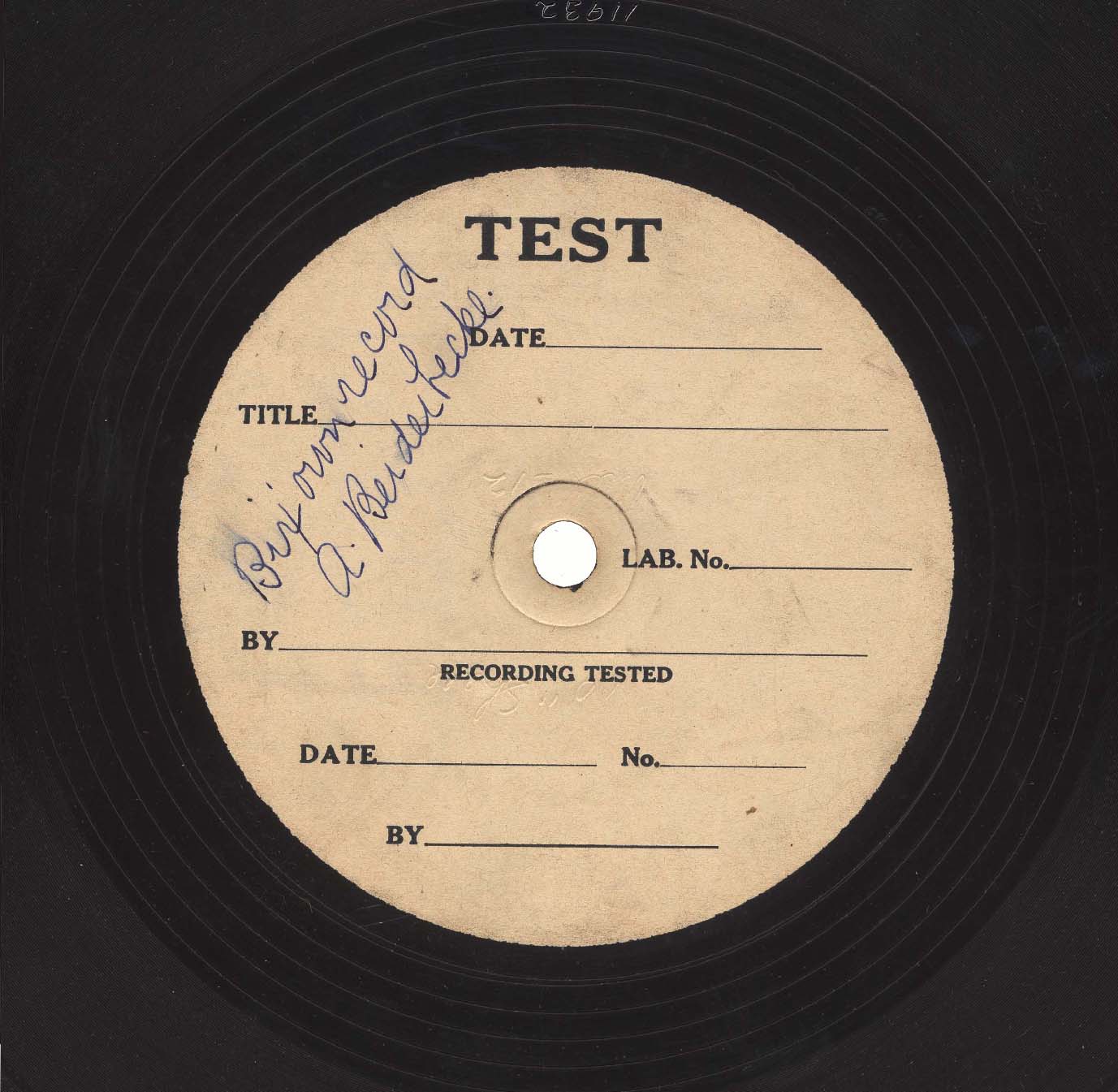

- Wolfe quotes Scott Black in pages

171-172: "There were no test pressings [that Bix was supposed to have

sent home to his parents."] The Institute of Jazz Studies has one

such test pressing with Bix's mother inscription.

The Coda. The

Culmination of the Book?

The Coda covers a lot of

unrelated subjects. Written in a disjointed manner, it fails to provide

an

appreciation of the most important aspect of Bix’s life: his remarkable

and

long-lasting music.

The coda begins with the

description of a (somewhat nauseating, in my

opinion) "reenactment of Bix and Hoagy's hot night listening to The

Firebird" in Barbara Wascher’s room in the Marriott, Tribute to Bix,

First, Wolfe mentions a

commotion in the “spinning room.”At this point

the negative comments about me begin to pile up:

What Wolfe has done is

highly unethical: Wolfe quotes the individual

who proposed the murder of Haim in

The Coda continues with

the interview, the morning after the Stravinsky

experiment, of an anonymous Bixophile. Wolfe reports, among other

things, the

Bixophile’s reaction to Bix’s arrest. He also throws in the unjustified

remark

that Rich Jonhson “was completely and totally in love with Bix.”

Then, Wolfe goes into

excruciating detail about what Barb told him

about The Firebird, throwing in, out of context, the names of Sarah

Ivens

(Bix’s arrest) and Gene Berton (the alleged fling with Bix). The

chronology of

events is confusing. As I understand it, there is a flaw:

- First the Firebird listening thing.

- Then the passage transcribed above.

- Then the interview of the unnamed individual (next morning).

- Then back to the Firebird thing the night before where "I was

depressed

but also strangely energized by the things the Bixophile had said [the

next

morning]."

The Bottom Line.

Individuals who know

little or nothing about Bix are not going to find in "Finding Bix"

objective information about his life and music. I venture to guess

that, if they have the patience to go through the book, most will be

turned away from Bix. Wolfe may have found himself, but surely he did

not recruit new Bixophiles.

Albert Haim, Stony

Brook, June 2017.

Note [1] There are six

mentions of the word calathumpic in “Finding Bix.”