Albert Lewis Petersen

Born September 4, 1865 – Died February 25, 1951

Guest Column by James Victor "Jim" Petersen

Vice President of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society

Introduction. By

Albert Haim.

Albert Petersen, known in the

Beiderbecke family as "Uncle Al," "Uncle Albert" or "Uncle Olie," was

related to Leon Bismark "Bix" Beiderbecke, the legendary

cornetist/pianist/composer from Davenport, Iowa. Albert Petersen was

married to Caroline "Carrie" May Kennedy, a cousin of Bix's mother,

Agatha. The Petersen and Beiderbecke families were not only relatives,

but close friends.

Albert Petersen was a distinguished musician. He founded the "Tri-City

Symphony," led the St. Ambrose University Band, and had his own

"Petersen" band that played at many functions in Davenport, and also

taught several instruments. His four sons all played

professionally at one time or another and his daughter played the

piano. Therefore, when Bix Beiderbecke, as a child, displayed an

unusual musical talent, Albert Petersen was consulted by Agatha.

Charles Burnett Beiderbecke, Bix's brother, wrote to Bix biographer

Philip R. Evans on June 1, 1960, "Uncle

Olie was the conductor of a brass band here in Davenport. He had three

sons [Note 1] who became better than average musicians. The oldest son,

piano; the middle one, cello, is still teaching and playing in our

Tri-City Symphony Orchestra; the youngest boy played the violin. Uncle

Olie readily saw Bix was full of music and gave him many valuable

tips. When he first took an interest in the Bix he tried him to get to

play violin. Bix rebelled, the cornet was his choice and there was no

changing his mind."

The interaction of Bix with

Albert Petersen is elaborated in the biography "Bix, Man and Legend" by

Richard M. Sudhalter and Philip R. Evans. Here are the sections of

Bix's biography that refer to Albert Petersen. [Note 2]

Agatha (Bix’s mother) soon sought expert

guidance in harnessing her son’s obvious talents. One of her

cousins was married to Albert Petersen, a competent cornetist and brass

band conductor known to the Beiderbecke children as “Uncle Olie”. (sic)

Three of his sons (actually four sons

and a daughter who all played at least one or more instruments and also

sang) had shown early promise, imparting to him the status of family

talent scout and arbiter of musical precocity. He dropped over

one day to hear Agatha’s seven-year-old-boy wonder go through his paces

(on the piano).

Uncle Olie could hardly contain his

enthusiasm. “Agatha, this boy has something.” He said.

“Keep me informed about his progress – and whatever you do, get him

some piano lessons.”

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Aggie, anxious to keep her son’s mind

occupied as he recovered (from scarlet fever), took Al Petersen’s

advice at last and engaged as piano teacher, Prof. Charles Grade

(Graw-deh) from Muscatine, 40 miles west of Davenport.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Bix kept plugging away on the cornet,

and by late spring had worked up enough confidence to approach Al

Petersen for advice. Uncle Olie, whatever his reasons, was less

than encouraging. “Why don’t you try the violin first, and get

yourself a good, solid musical foundation?” was the substance of his

reply. Bix went home and practiced some more, dodging his

mother’s questions about the session with Uncle Olie. He never

mentioned it again.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Aggie Beiderbecke, pondering her

son’s future, had begun to come to terms with a number of

all-too-apparent realities. Not only was it clear that he was

hell-bent on becoming a professional musician despite any opposition

she or Bismark (Bix’s Father) might mount, but, even more important, he

was clearly very good at what he did and in growing demand among

orchestras specializing in his music. It was not her or

Bismark’s, nor that of Ernest Otto, or Prof. Koepke or Uncle Olie

Petersen. But music it was, and Bix’s failure to win a union card

– and the musical respect that went with it – in his own home

town was hurting him. It was, she reflected, keeping him away

from home when he could be playing around the tri-cities area, and it

already cost him a number of good opportunities . He had lost the

Terrace Gardens job, the Majestic, the Capitol and heaven knew how many

others, simply because the grayer heads of Local 67 would not accept

the possibility that a “jazzer” could be a musician too.

Aggie telephoned Al Petersen and

asked her cousin to have a chat with the gentleman of the examining

board, Roy Kautz included. “I thought it might be easier for Bix here

than in Chicago,” was her explanation in later years. Uncle Olie,

far from entirely convinced but in this case allowing family loyalty to

dominate, made a point of talking to board members Ben Ebeling, Ernest

Otto and Frank Fich immediately about young Beiderbecke.

“The kid may be light on reading

music,” he said, “but he does have some talent as a jazzer. Be

too bad to turn him down again.” After lengthy and heated discussions,

and not a little grumbling, he won their assent to examine the “jazzer”

again. Come Monday, the first of October, Bix Beiderbecke turned up,

neat and smiling – and hornless – at the union audition hall.

“Where’s the cornet, Bix?” Ebeling

asked, perplexed. Bix grinned.

“Oh, that. Hope you don’t mind, but I

thought I’d take the exam on the piano”. Whereupon he seated

himself at the keyboard, playing through two “light” classical

selections, and passed without so much as a question from the

thunderstruck examiners.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(About Bix’s playing on “Singing the

Blues”)

The tone was that of the brass band

cornetist, of Uncle Olie Petersen and all he valued – clean, ringing,

every note struck head-on, with none of the half valved effects,

growls, buzzes or other “dirty” tricks common to black brass

soloists. It functioned best not in the blues idiom, but on songs

with appealing melodies and interesting chord structures, paraphrasing

a given melodic line into new, usually superior one bearing the natural

structure of “correlated” phrasing.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Note 1. Albert Petersen had

four sons and a daughter: Vinceno Albert, Arthur Alexander, Harry

Alonzo, Victor Herbert and Helen Margaret.

Note 2. The relevant excerpts from Sudhalter and Evans were prepared by

Jim Petersen.

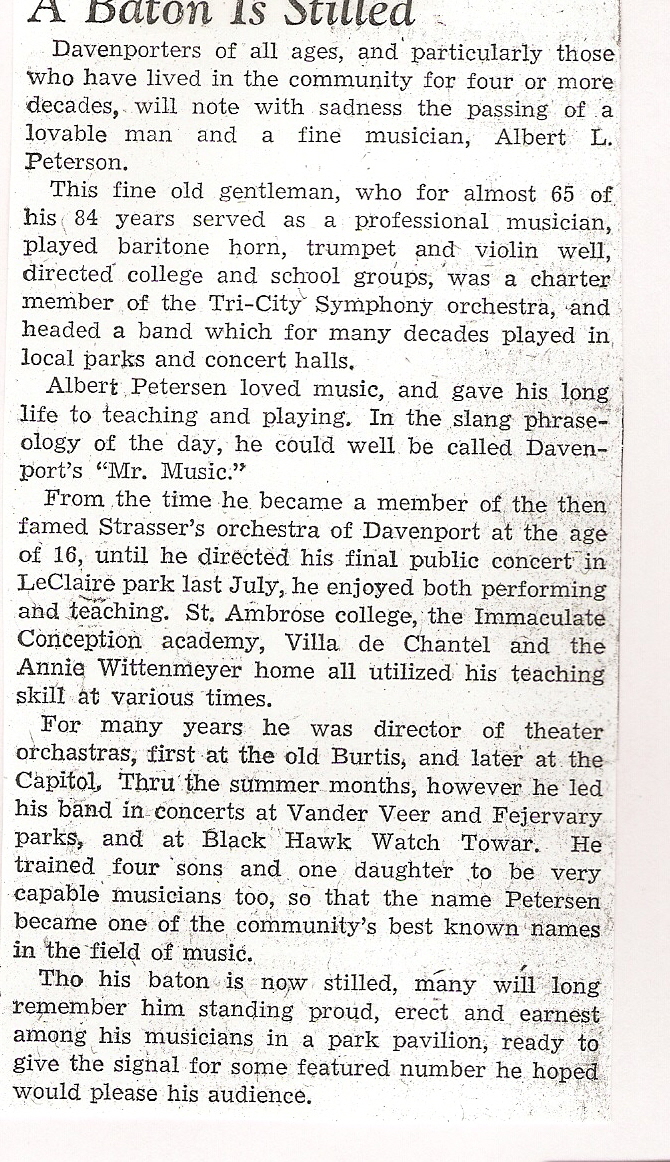

A Brief Biography of Albert Petersen. By Jim Petersen,

Albert's Grandson.

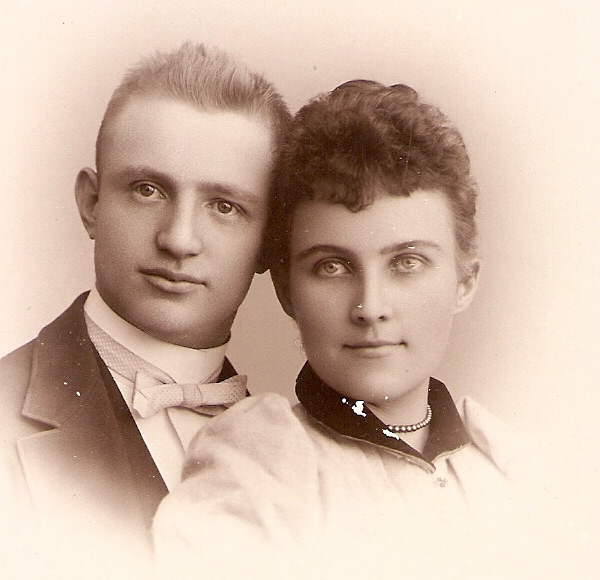

Albert Petersen was born

in Struxdorf, Schleswig-Holstein Germany on September 4th

1865. While he always considered himself to be of German

heritage, his grandson traced back the family lineage to be that of

Danish origins. He and his parents moved to America when Albert

was only two years old. He was married to Carrie Kennedy, Agatha

Beiderbecke’s first cousin and friend. The Petersen and

Beiderbecke families were friends. The Beiderbecke children knew

Albert Petersen as “Uncle Albert”, the source for the belief that he

was known as “Uncle Olie” cannot be substantiated at this time.

At the age of 16 Albert joined the Strasser Orchestra as a horn player

and by age 17 was assistant concert master. At the age of 18 he

directed the orchestra in the former Burtis Opera House, playing for

the most notable actresses and actors in show business. He also

directed orchestras at other performance venues in the Quad City area.

He provided an orchestra to play background music for silent films at

the old Grand theater, and his own “Har-Cen-Art” theater as well.

In 1891 at the age of 26 he started his own band and orchestra that

numbered as many as 40 members. The “Petersen Band” stayed together and

played for over 50 years. He also married Carolyn (Carrie)

Kennedy that year, who was a first cousin to Bix Beiderbecke’s mother

Agatha.

In 1895 after helping to lay the cornerstone for the first building of

St. Ambrose College (today’s St. Ambrose University), Albert formed

that institutions first band from scratch! After determining the

need for a band, the college ordered sixteen instruments, but when they

arrived in the fall of that year they found that there were no

musicians on campus to play them. So, “all likely candidates were

called in” and the instruments were divided up amongst them according

to fine musical details like who had big or small lips, who had strong

front teeth, or who liked big shiny new brass instruments.

Reports have it that the first sounds of the new band were rather

“unique”, and that the new band students were ordered to practice out

in the back pasture so as not to disturb scholarly endeavors on

campus. But by the following May, Albert Petersen had them

playing well enough to perform at Commencement and other concerts as

well. Albert directed the band from 1895 to 1898 and was pressed

into service again from 1901 to 1906.

He also taught and formed the bands at the St. Vincent and Annie

Wettenmyer Orphanages and gave private lessons to many successful

musicians over the years including his four sons and one

daughter. Albert himself played trumpet, violin and viola; his

son Ceno played piano (and made a living as a piano tuner and

performer), Art played the cello and was active in the Musicians Union

as an officer most of this life, Helen played the piano and sang,

Harry played violin and played with the Lawrence Welk orchestra, and

his youngest son Victor who sang, played cornet in his Dad’s

“Petersen Band” and violin in the Tri-City Symphony and who went on to

be a talented violin maker and stringed instrument repairmen for many

years. Albert’s sons all went on to play professionally at one time or

another.

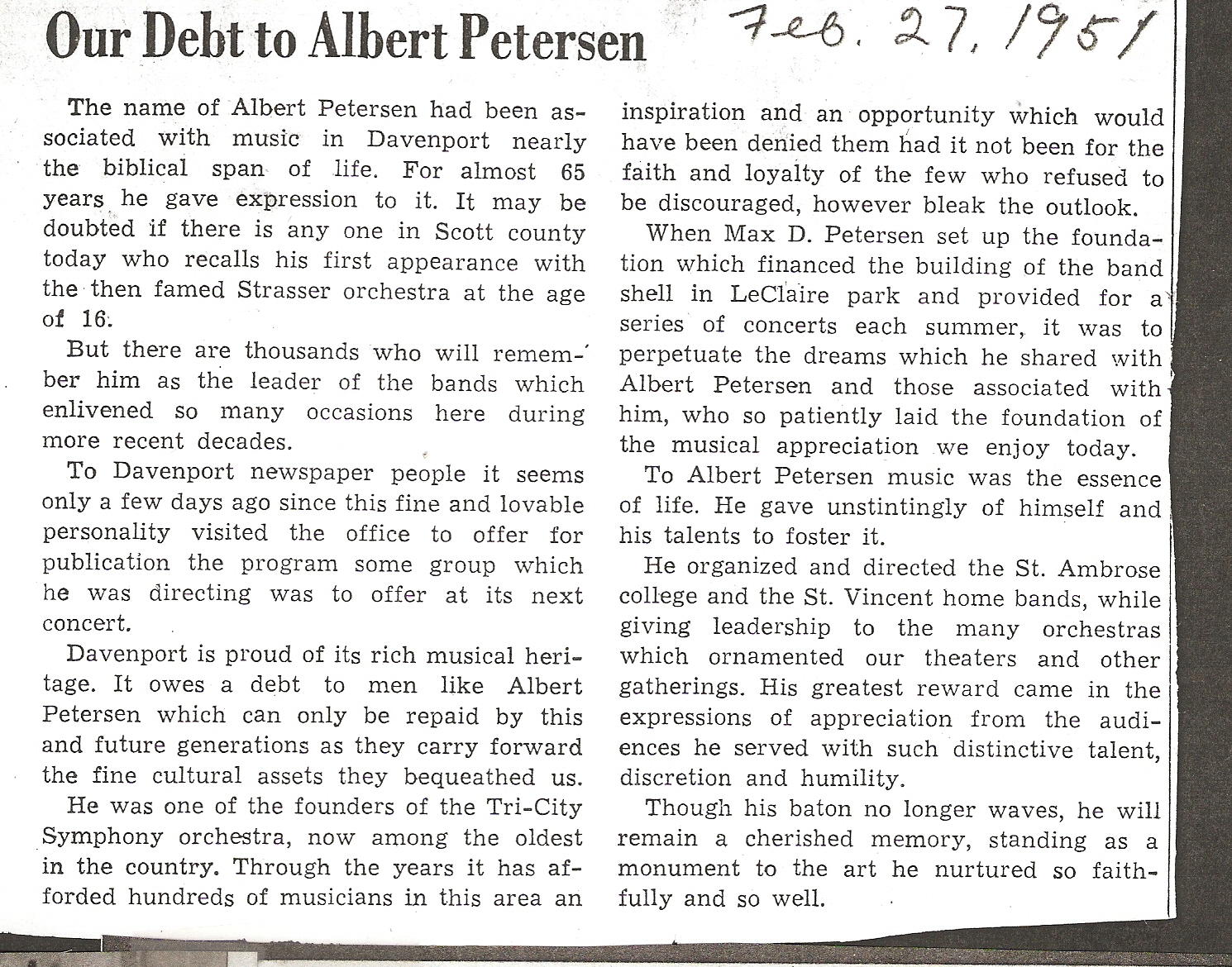

The Tri-City Symphony (today’s Quad City Symphony) was organized and

founded by Albert Petersen and others in 1915. At the time the Quad

City area was the smallest area to have a full Symphony Orchestra in

the U. S.. It now holds the distinction of being one of the

oldest continuous Symphony Orchestra’s in the country.

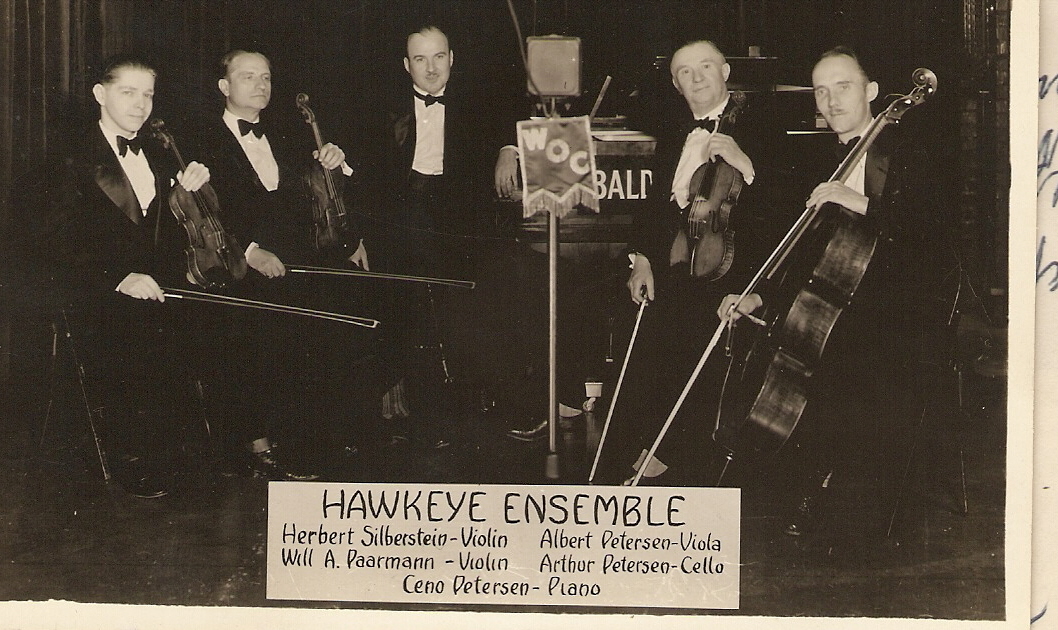

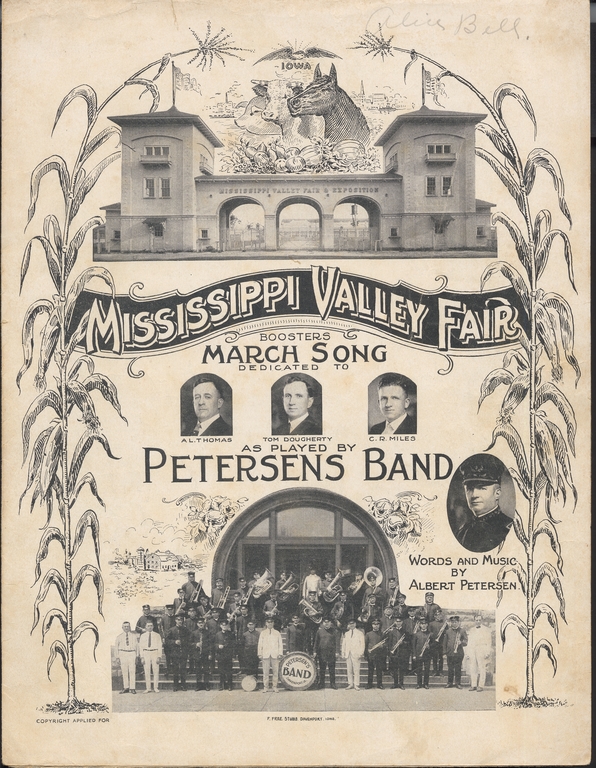

1915 was a busy year, as Albert and his son Art performed in the

“Blackhawk Hotel Ensemble” for their Grand opening in the Gold Room

(home venue for the 40th Bix Festival in 2011). His son’s Art and

Ceno played on the radio with the Giezzela Weber trio, Albert’s Hawkeye

Ensemble did likewise. Albert and his son Ceno wrote music for various

businesses in the area, including the Mississippi Valley Fair.

The Davenport German community had a very nice park at the edge of town

called Schuetzen Park. The area was predominantly German and

there were also several “Turner” halls for socializing and exercising

in the area. Albert and his family members were actively involved

with these groups. At the time of the first World War, when Bix

Beiderbecke insisted that he not be called Leon “Bismark”, anti German

sentiment naturally arose.

One night in 1917, two fellows, one of which Albert knew, stopped by

his home at 704 West Locust and started to accuse him of being helpful

somehow or sympathetic to the German’s in the war. Albert, a

kindly, gentle and patient person, didn’t take the accusation

well. He said, “I’m an American!” “You know me as well as

you do and you ask this?” “I’m insulted and I ask you to leave or

me and my sons will throw you off this porch!” They quickly

apologized and all was forgiven a short while later. Soon after,

the Stars and Stripes Forever by John Philip Sousa ended most

performances.

As mentioned in Richard Sudhalter's and Philip Evans' “Bix, Man and

Legend,” Albert advised Bix Beiderbecke that the $35 price was fair for

his first “good” cornet from Fritz Putzier. At some point, Albert

asked Bix to play for him. Albert said, “You play very well, but

I guess I don’t understand your music”. Uncle Albert (as he was

known to the Beiderbecke’s) was the one who suggested Bix get some

formal training when he heard him play the piano at the age of 7.

When Max D. Petersen (no relation) decided to sponsor the

building of a European style band shell on the Mississippi River in

LeClaire Park in 1925, his friend Albert Petersen was consulted.

Albert directed the orchestra’s that played the outdoor concert series

in that park and other pavilions around the area for 39 continuous

years right up to six months before his death at the age of 85 in

1951. His son Art, who had been the announcer for the orchestra

took over as conductor and his youngest son Victor took over the

announcing chores.

Having just improved (converted an outdoor theater to an indoor one)

the Har-Cen-Art theater he owned, he also purchased the “Victor”

theater. The Har-Cen-Art was on Harrison Street, and the parts of

the theater’s name represented the names of his three sons, Harry, Ceno

and Art. When he purchased the “Victor” he named it after his

youngest son. As fate would have it, the Great Depression came

along and business took a nose dive. Albert choose to give up his

theaters in favor of keeping his band going as he said, “The band

members need the work and the community needs the music more now than

ever.”

Albert and his family attended Bix’s funeral in 1931. While he

and others in the Petersen family didn’t always understand Bix’s music

or why he’d want to travel, play in speakeasys, and be involved with

illegal drinking, they always liked Bix the person and tears were shed

upon his passing. Albert was to have an even greater sadness when

he lost both his beloved wife and his son Ceno in 1949.

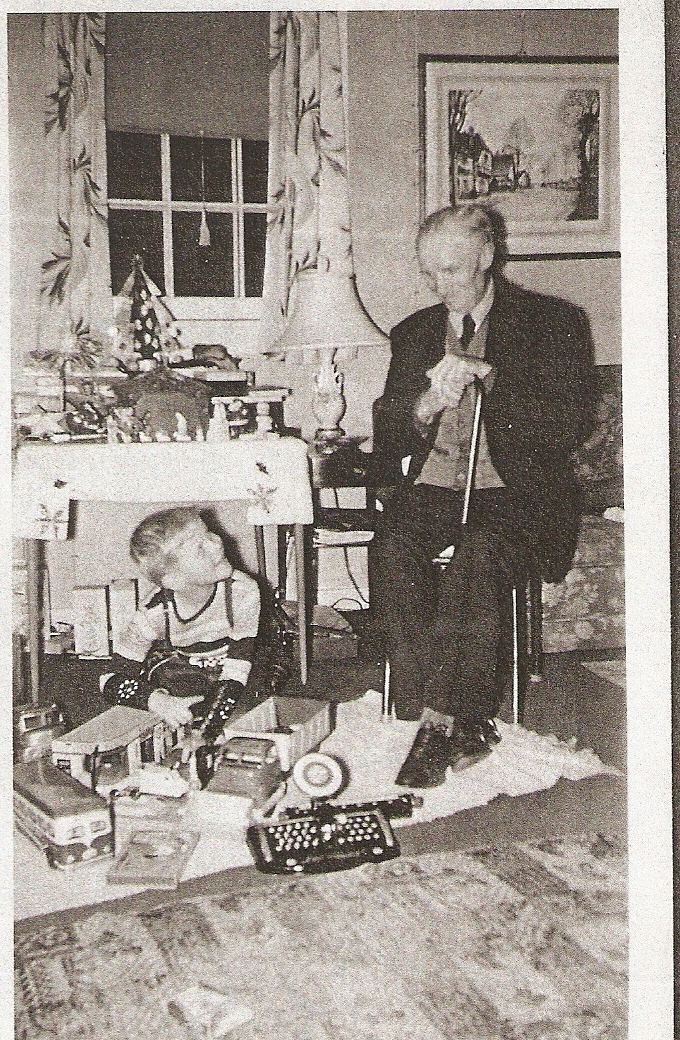

Albert’s grandson, the late Vince Petersen (Ceno’s son), a retired

first violinist with the Symphony once said, “I kind of thought Bix

might be over rated…but then I heard one of his records and that

promptly changed my mind and I wanted to hear more.”

Everyone in the Petersen family loved their wonderful patriarch

Albert. One late afternoon when Bix Beiderbecke Society Vice

President Jim Petersen was riding with his parents and grandfather on

their way to Harry Petersen’s house for dinner in Moline, Albert made a

request. “Since we are a little early, could we stop at the

Moline Turner Hall just for a minute to see if anyone I know is

there?” Victor said, “Why sure Pa, I’ll go in with you.”

After a few minutes, Victor came out and he was dabbing at his eyes

with a handkerchief. “What’s wrong Vic?” came the inquiry from

his concerned wife Violet.

“Nothing” came the reply. “It’s just that every man in that place

stood up and came over and shook Pa’s hand and said how great it was to

see him, it just touched me to see the look in their eyes and the look

in Pa’s eyes too”. He may not have known all of them, but

they sure knew him. Many others loved Albert L. Petersen too …..

Gallery of Photographs. From

Jim Petersen's collection.